Back to BlogCustomization Process

Why Your Approved Corporate Gift Box Sample Won't Match Mass Production

2026-01-27

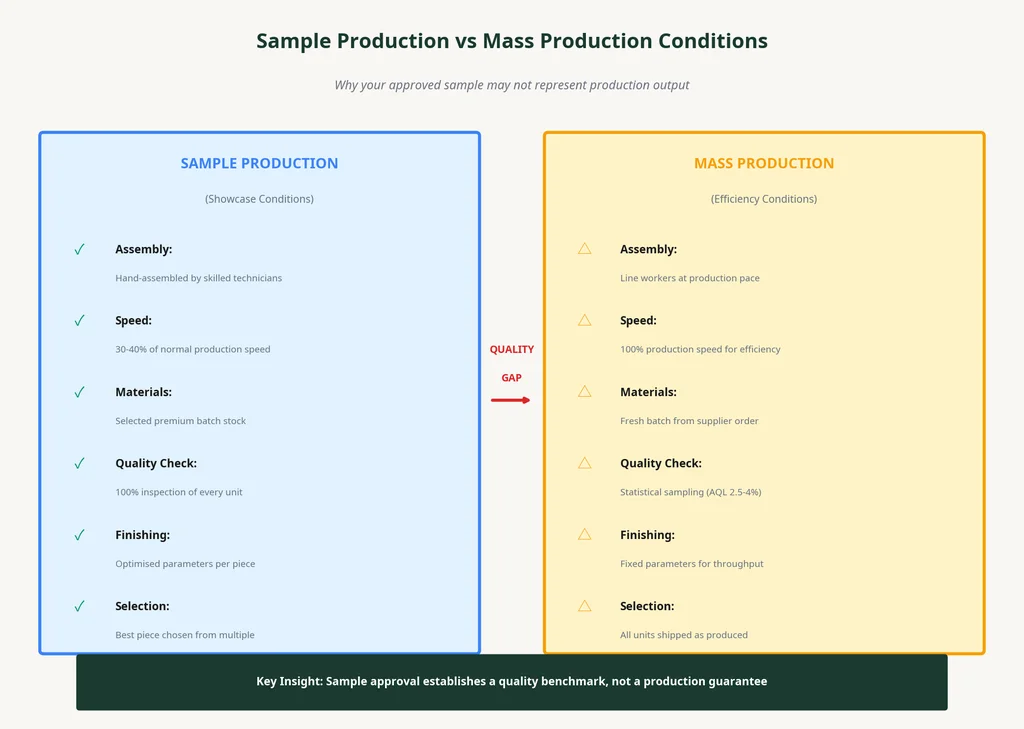

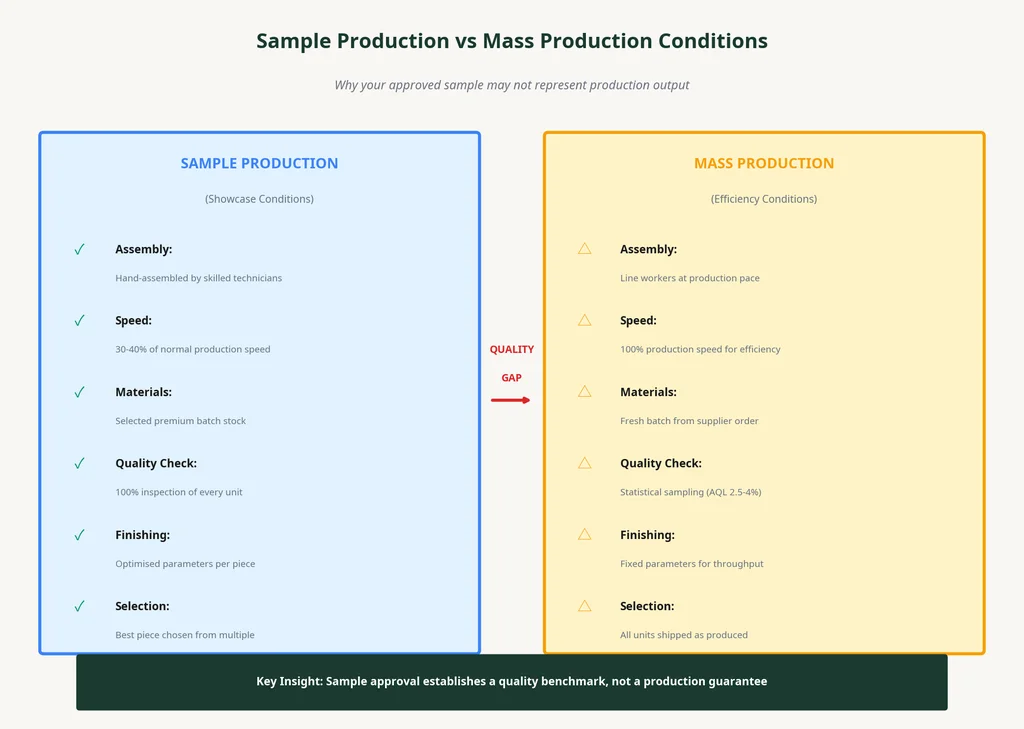

When procurement teams approve a physical sample from their supplier, there's a natural assumption that mass production will deliver identical results. The sample has been reviewed, the quality has been verified, and the procurement manager has confirmed that it meets the specifications in the purchase order. The assumption is straightforward: if the sample looks right, the production run will look right. In practice, the gap between "sample approved" and "production delivered" exists because of fundamental differences in how samples and production runs are manufactured—differences that are rarely disclosed during the approval process and almost never reflected in the supplier's quality assurance documentation. The result is a systematic expectation mismatch that surfaces only when the production shipment arrives and looks noticeably different from the approved sample.

The misjudgment begins with how samples are produced in the custom packaging industry. When a supplier creates a sample for a corporate gift box project, the sample is typically manufactured under conditions that cannot be replicated at production scale. Sample boxes are often hand-assembled by skilled technicians who take significantly more time per unit than production line workers. The paper stock used for samples may come from a different batch than the paper stock that will be used for production—a batch that was specifically selected for its visual consistency and surface quality. The printing process for samples is often run at slower speeds, which allows for tighter registration, more accurate colour matching, and cleaner finishing. The foil stamping, embossing, and lamination processes are performed with more care and attention to detail than is economically feasible during a production run of 5,000 or 50,000 units. The sample that the procurement team approves is, in effect, a showcase piece—a demonstration of what the supplier can achieve under ideal conditions, not a representative example of what the production run will deliver.

The material batch variation between samples and production is one of the most significant sources of visual discrepancy. Paper and board materials are manufactured in batches, and each batch has slight variations in colour, texture, surface smoothness, and ink absorption characteristics. When a supplier creates a sample, they typically use materials from their current stock—materials that may have been in inventory for weeks or months. When the production run begins, the supplier orders fresh materials from their paper supplier, and these materials come from a different batch. The colour of the board may be slightly warmer or cooler. The surface texture may be slightly rougher or smoother. The ink absorption rate may be slightly higher or lower. These variations are within the paper manufacturer's tolerance specifications, but they are visible to the human eye—particularly when the production boxes are placed next to the approved sample. The procurement team sees a colour shift, a texture difference, or a print quality variation and concludes that the supplier has failed to meet the agreed specifications. In reality, the supplier has met the material specifications exactly—the specifications simply don't guarantee visual consistency across batches.

The printing process differences between sample production and mass production create another layer of visual variation. When a supplier prints a sample, the press operator can take time to adjust ink density, registration, and colour balance until the output matches the design proof exactly. The press may run at 30-40% of its normal speed, which allows for more precise ink transfer and sharper image reproduction. The operator may print several test sheets and select the best one to use as the sample. During production, the press runs at full speed to meet the delivery deadline and maintain cost efficiency. The operator makes adjustments at the start of the run, but once production is underway, there is limited opportunity for fine-tuning. The first 50-100 sheets of a production run are typically considered "make-ready" sheets—sheets that are used to calibrate the press and are not included in the final shipment. The remaining sheets are printed at production speed, and while they meet the supplier's quality control standards, they may not match the sample exactly. The colours may be slightly more saturated or slightly less saturated. The registration may be slightly off on some sheets. The ink coverage may be slightly uneven in areas of heavy coverage. These variations are within industry tolerances, but they are visible when compared to the hand-selected sample.

The finishing process variations are particularly noticeable in premium corporate gift boxes that feature foil stamping, embossing, or specialty coatings. Foil stamping involves transferring metallic or pigmented foil onto the substrate using heat and pressure. The quality of the foil transfer depends on the temperature, pressure, dwell time, and the surface characteristics of the substrate. When a supplier creates a sample, the foil stamping operator can take time to optimise these parameters for the specific substrate being used. During production, the foil stamping machine runs at higher speeds, and the parameters are set for efficiency rather than perfection. The result is that foil coverage may be slightly less complete on production units—there may be small areas where the foil has not transferred fully, or the edges of the foil may be slightly less crisp. Embossing quality is similarly affected by production speed. A sample may feature deep, well-defined embossing with crisp edges, while production units may have slightly shallower embossing with softer edges. Specialty coatings such as soft-touch lamination, spot UV, and textured finishes are also subject to variation based on production speed, material batch, and environmental conditions during application.

The colour matching challenge is compounded by the difference between digital proofs and physical samples. When a procurement team reviews a digital proof, they are looking at a representation of the design on their computer screen or printed on their office printer. The colours they see are determined by their screen calibration, ambient lighting, and the colour profile of the proof file. When the physical sample arrives, the colours may look different because the sample is printed on actual substrate using actual inks, which behave differently than the digital simulation. The procurement team approves the sample because it looks "close enough" to the digital proof, without realising that the sample itself may not be representative of production output. When the production run arrives, the colours may be different from both the digital proof and the sample—different from the digital proof because of the inherent limitations of digital colour simulation, and different from the sample because of material batch variation and production speed effects.

The printing process differences between sample production and mass production create another layer of visual variation. When a supplier prints a sample, the press operator can take time to adjust ink density, registration, and colour balance until the output matches the design proof exactly. The press may run at 30-40% of its normal speed, which allows for more precise ink transfer and sharper image reproduction. The operator may print several test sheets and select the best one to use as the sample. During production, the press runs at full speed to meet the delivery deadline and maintain cost efficiency. The operator makes adjustments at the start of the run, but once production is underway, there is limited opportunity for fine-tuning. The first 50-100 sheets of a production run are typically considered "make-ready" sheets—sheets that are used to calibrate the press and are not included in the final shipment. The remaining sheets are printed at production speed, and while they meet the supplier's quality control standards, they may not match the sample exactly. The colours may be slightly more saturated or slightly less saturated. The registration may be slightly off on some sheets. The ink coverage may be slightly uneven in areas of heavy coverage. These variations are within industry tolerances, but they are visible when compared to the hand-selected sample.

The finishing process variations are particularly noticeable in premium corporate gift boxes that feature foil stamping, embossing, or specialty coatings. Foil stamping involves transferring metallic or pigmented foil onto the substrate using heat and pressure. The quality of the foil transfer depends on the temperature, pressure, dwell time, and the surface characteristics of the substrate. When a supplier creates a sample, the foil stamping operator can take time to optimise these parameters for the specific substrate being used. During production, the foil stamping machine runs at higher speeds, and the parameters are set for efficiency rather than perfection. The result is that foil coverage may be slightly less complete on production units—there may be small areas where the foil has not transferred fully, or the edges of the foil may be slightly less crisp. Embossing quality is similarly affected by production speed. A sample may feature deep, well-defined embossing with crisp edges, while production units may have slightly shallower embossing with softer edges. Specialty coatings such as soft-touch lamination, spot UV, and textured finishes are also subject to variation based on production speed, material batch, and environmental conditions during application.

The colour matching challenge is compounded by the difference between digital proofs and physical samples. When a procurement team reviews a digital proof, they are looking at a representation of the design on their computer screen or printed on their office printer. The colours they see are determined by their screen calibration, ambient lighting, and the colour profile of the proof file. When the physical sample arrives, the colours may look different because the sample is printed on actual substrate using actual inks, which behave differently than the digital simulation. The procurement team approves the sample because it looks "close enough" to the digital proof, without realising that the sample itself may not be representative of production output. When the production run arrives, the colours may be different from both the digital proof and the sample—different from the digital proof because of the inherent limitations of digital colour simulation, and different from the sample because of material batch variation and production speed effects.

The supplier's material substitution practices are another source of sample-to-production discrepancy that is rarely disclosed to procurement teams. When a supplier creates a sample, they may use premium materials from their inventory to showcase their best work. When the production order is placed, the supplier may substitute materials that meet the same specifications but come from different sources or have different characteristics. For example, a supplier may use virgin paper stock for the sample but mechanically recycled paper stock for production—both meet the "300gsm coated board" specification, but the recycled stock may have visible speckling or a slightly different colour tone. A supplier may use a premium soft-touch lamination film for the sample but a standard soft-touch film for production—both provide a soft-touch finish, but the premium film has a smoother, more luxurious feel. These substitutions are not necessarily deceptive—they may be driven by material availability, cost pressures, or sustainability commitments—but they result in production output that looks and feels different from the approved sample.

The environmental conditions during production can also affect the visual consistency of corporate gift boxes. Paper and board materials are hygroscopic—they absorb and release moisture based on the humidity of their environment. A sample produced in a climate-controlled facility during the dry season may have different characteristics than a production run manufactured during the humid season. The board may be slightly softer, the ink may absorb differently, and the lamination may adhere with different characteristics. These environmental effects are within normal manufacturing tolerances, but they contribute to the cumulative visual difference between samples and production output. Suppliers in the UK and Europe are particularly aware of these seasonal variations, as humidity levels can vary significantly between summer and winter months.

The quality control standards applied to samples versus production runs are fundamentally different. When a supplier creates a sample, the quality control process is essentially 100% inspection—every aspect of the sample is reviewed and verified before it is sent to the client. If the sample has any defect, it is discarded and a new sample is created. During production, quality control is based on statistical sampling—a percentage of units are inspected, and the batch is accepted or rejected based on the results of the sample inspection. The Acceptable Quality Level (AQL) for custom packaging typically allows for 2.5-4% defects in a production batch, depending on the defect severity classification. This means that a production shipment of 5,000 units may contain 125-200 units with minor defects—units that would never have been sent as samples but are acceptable within production quality standards. When the procurement team receives the shipment and inspects the units, they may find defects that were not present in the approved sample, leading to the conclusion that the supplier has failed to maintain quality standards.

The business impact of sample-to-production discrepancy extends beyond aesthetic disappointment—it can affect brand perception, recipient experience, and the success of the corporate gifting programme. When a procurement team approves a sample, they are making a commitment to their internal stakeholders about the quality of the gift boxes that will be delivered. If the production run does not match the sample, the procurement team must decide whether to accept the shipment, request rework, or reject the order entirely. Accepting a shipment that does not match the sample may damage the company's brand perception if the gift boxes are distributed to clients or employees who notice the quality difference. Requesting rework delays the delivery and may not fully resolve the quality issues. Rejecting the order creates a crisis—the corporate event is approaching, and there is no time to source alternative gift boxes. The procurement team is left with no good options, and the supplier relationship may be damaged regardless of the outcome.

When planning custom corporate gift box projects, it's essential to understand that sample approval establishes a quality benchmark, not a production guarantee. For comprehensive guidance on managing the customization process from concept through delivery—including strategies for specifying quality requirements that translate to production—refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial design through final delivery.

The practical solution for procurement teams is to establish explicit quality specifications that go beyond "match the sample." Instead of relying on sample approval as the sole quality benchmark, procurement teams should specify acceptable tolerances for colour variation (using Delta E measurements), material characteristics (including specific paper grades and sources), finishing quality (including foil coverage percentage and embossing depth), and defect rates (using AQL standards). These specifications should be included in the purchase order and agreed upon by the supplier before production begins. The procurement team should also request a pre-production sample—a sample produced using the actual materials and processes that will be used for the production run—rather than relying on a showcase sample produced under ideal conditions. This pre-production sample provides a more accurate preview of what the production output will look like and allows the procurement team to identify and address any quality concerns before the full production run is completed.

The supplier relationship management aspect of sample-to-production quality is often overlooked by procurement teams. Suppliers are not trying to deceive their clients by producing samples that exceed production quality—they are trying to win the business by showcasing their best work. The disconnect between sample quality and production quality is a structural feature of the custom packaging industry, not a failure of individual suppliers. Procurement teams who understand this dynamic can work more effectively with their suppliers by setting realistic expectations, specifying explicit quality requirements, and building quality verification checkpoints into the production process. By treating sample approval as the beginning of a quality management process rather than the end, procurement teams can reduce the risk of sample-to-production discrepancy and ensure that the final delivery meets their expectations.

The documentation and communication practices around sample approval are critical to managing expectations. When a procurement team approves a sample, they should document exactly what they are approving—the colour, the material feel, the finishing quality, the structural integrity—and communicate these expectations to the supplier in writing. The supplier should confirm that these characteristics can be maintained at production scale, or disclose any expected variations. This documentation creates a shared understanding of quality expectations and provides a reference point for quality disputes if they arise. Without explicit documentation, the procurement team's expectations are based on their subjective interpretation of the sample, and the supplier's commitments are based on their standard production capabilities. The gap between these interpretations is where quality disputes originate.

The timeline implications of sample-to-production quality management are significant. If a procurement team wants to verify production quality before the full shipment is delivered, they need to build time into the project schedule for pre-production samples, quality review, and potential adjustments. A pre-production sample typically adds 1-2 weeks to the project timeline—time for the supplier to source production materials, produce a sample using production processes, ship the sample to the client, and receive approval. If the pre-production sample reveals quality issues, additional time is needed for the supplier to make adjustments and produce a revised sample. Procurement teams who do not build this time into their project schedules are forced to accept production output without verification, which increases the risk of quality disappointment. The choice is between investing time upfront in quality verification or accepting the risk of quality issues at delivery.

The cost implications of sample-to-production quality management should also be considered. Pre-production samples, explicit quality specifications, and quality verification checkpoints all add cost to the project—cost that may be absorbed by the supplier, passed on to the buyer, or shared between both parties. Procurement teams should discuss these costs with their suppliers during the quotation process and make informed decisions about the level of quality assurance they require. For high-visibility corporate gifting programmes where brand perception is critical, the additional cost of quality verification is a worthwhile investment. For lower-stakes projects where minor quality variations are acceptable, the standard sample approval process may be sufficient. The key is to make this decision consciously, based on a clear understanding of the risks and trade-offs, rather than assuming that sample approval guarantees production quality.

The supplier's material substitution practices are another source of sample-to-production discrepancy that is rarely disclosed to procurement teams. When a supplier creates a sample, they may use premium materials from their inventory to showcase their best work. When the production order is placed, the supplier may substitute materials that meet the same specifications but come from different sources or have different characteristics. For example, a supplier may use virgin paper stock for the sample but mechanically recycled paper stock for production—both meet the "300gsm coated board" specification, but the recycled stock may have visible speckling or a slightly different colour tone. A supplier may use a premium soft-touch lamination film for the sample but a standard soft-touch film for production—both provide a soft-touch finish, but the premium film has a smoother, more luxurious feel. These substitutions are not necessarily deceptive—they may be driven by material availability, cost pressures, or sustainability commitments—but they result in production output that looks and feels different from the approved sample.

The environmental conditions during production can also affect the visual consistency of corporate gift boxes. Paper and board materials are hygroscopic—they absorb and release moisture based on the humidity of their environment. A sample produced in a climate-controlled facility during the dry season may have different characteristics than a production run manufactured during the humid season. The board may be slightly softer, the ink may absorb differently, and the lamination may adhere with different characteristics. These environmental effects are within normal manufacturing tolerances, but they contribute to the cumulative visual difference between samples and production output. Suppliers in the UK and Europe are particularly aware of these seasonal variations, as humidity levels can vary significantly between summer and winter months.

The quality control standards applied to samples versus production runs are fundamentally different. When a supplier creates a sample, the quality control process is essentially 100% inspection—every aspect of the sample is reviewed and verified before it is sent to the client. If the sample has any defect, it is discarded and a new sample is created. During production, quality control is based on statistical sampling—a percentage of units are inspected, and the batch is accepted or rejected based on the results of the sample inspection. The Acceptable Quality Level (AQL) for custom packaging typically allows for 2.5-4% defects in a production batch, depending on the defect severity classification. This means that a production shipment of 5,000 units may contain 125-200 units with minor defects—units that would never have been sent as samples but are acceptable within production quality standards. When the procurement team receives the shipment and inspects the units, they may find defects that were not present in the approved sample, leading to the conclusion that the supplier has failed to maintain quality standards.

The business impact of sample-to-production discrepancy extends beyond aesthetic disappointment—it can affect brand perception, recipient experience, and the success of the corporate gifting programme. When a procurement team approves a sample, they are making a commitment to their internal stakeholders about the quality of the gift boxes that will be delivered. If the production run does not match the sample, the procurement team must decide whether to accept the shipment, request rework, or reject the order entirely. Accepting a shipment that does not match the sample may damage the company's brand perception if the gift boxes are distributed to clients or employees who notice the quality difference. Requesting rework delays the delivery and may not fully resolve the quality issues. Rejecting the order creates a crisis—the corporate event is approaching, and there is no time to source alternative gift boxes. The procurement team is left with no good options, and the supplier relationship may be damaged regardless of the outcome.

When planning custom corporate gift box projects, it's essential to understand that sample approval establishes a quality benchmark, not a production guarantee. For comprehensive guidance on managing the customization process from concept through delivery—including strategies for specifying quality requirements that translate to production—refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial design through final delivery.

The practical solution for procurement teams is to establish explicit quality specifications that go beyond "match the sample." Instead of relying on sample approval as the sole quality benchmark, procurement teams should specify acceptable tolerances for colour variation (using Delta E measurements), material characteristics (including specific paper grades and sources), finishing quality (including foil coverage percentage and embossing depth), and defect rates (using AQL standards). These specifications should be included in the purchase order and agreed upon by the supplier before production begins. The procurement team should also request a pre-production sample—a sample produced using the actual materials and processes that will be used for the production run—rather than relying on a showcase sample produced under ideal conditions. This pre-production sample provides a more accurate preview of what the production output will look like and allows the procurement team to identify and address any quality concerns before the full production run is completed.

The supplier relationship management aspect of sample-to-production quality is often overlooked by procurement teams. Suppliers are not trying to deceive their clients by producing samples that exceed production quality—they are trying to win the business by showcasing their best work. The disconnect between sample quality and production quality is a structural feature of the custom packaging industry, not a failure of individual suppliers. Procurement teams who understand this dynamic can work more effectively with their suppliers by setting realistic expectations, specifying explicit quality requirements, and building quality verification checkpoints into the production process. By treating sample approval as the beginning of a quality management process rather than the end, procurement teams can reduce the risk of sample-to-production discrepancy and ensure that the final delivery meets their expectations.

The documentation and communication practices around sample approval are critical to managing expectations. When a procurement team approves a sample, they should document exactly what they are approving—the colour, the material feel, the finishing quality, the structural integrity—and communicate these expectations to the supplier in writing. The supplier should confirm that these characteristics can be maintained at production scale, or disclose any expected variations. This documentation creates a shared understanding of quality expectations and provides a reference point for quality disputes if they arise. Without explicit documentation, the procurement team's expectations are based on their subjective interpretation of the sample, and the supplier's commitments are based on their standard production capabilities. The gap between these interpretations is where quality disputes originate.

The timeline implications of sample-to-production quality management are significant. If a procurement team wants to verify production quality before the full shipment is delivered, they need to build time into the project schedule for pre-production samples, quality review, and potential adjustments. A pre-production sample typically adds 1-2 weeks to the project timeline—time for the supplier to source production materials, produce a sample using production processes, ship the sample to the client, and receive approval. If the pre-production sample reveals quality issues, additional time is needed for the supplier to make adjustments and produce a revised sample. Procurement teams who do not build this time into their project schedules are forced to accept production output without verification, which increases the risk of quality disappointment. The choice is between investing time upfront in quality verification or accepting the risk of quality issues at delivery.

The cost implications of sample-to-production quality management should also be considered. Pre-production samples, explicit quality specifications, and quality verification checkpoints all add cost to the project—cost that may be absorbed by the supplier, passed on to the buyer, or shared between both parties. Procurement teams should discuss these costs with their suppliers during the quotation process and make informed decisions about the level of quality assurance they require. For high-visibility corporate gifting programmes where brand perception is critical, the additional cost of quality verification is a worthwhile investment. For lower-stakes projects where minor quality variations are acceptable, the standard sample approval process may be sufficient. The key is to make this decision consciously, based on a clear understanding of the risks and trade-offs, rather than assuming that sample approval guarantees production quality.

The printing process differences between sample production and mass production create another layer of visual variation. When a supplier prints a sample, the press operator can take time to adjust ink density, registration, and colour balance until the output matches the design proof exactly. The press may run at 30-40% of its normal speed, which allows for more precise ink transfer and sharper image reproduction. The operator may print several test sheets and select the best one to use as the sample. During production, the press runs at full speed to meet the delivery deadline and maintain cost efficiency. The operator makes adjustments at the start of the run, but once production is underway, there is limited opportunity for fine-tuning. The first 50-100 sheets of a production run are typically considered "make-ready" sheets—sheets that are used to calibrate the press and are not included in the final shipment. The remaining sheets are printed at production speed, and while they meet the supplier's quality control standards, they may not match the sample exactly. The colours may be slightly more saturated or slightly less saturated. The registration may be slightly off on some sheets. The ink coverage may be slightly uneven in areas of heavy coverage. These variations are within industry tolerances, but they are visible when compared to the hand-selected sample.

The finishing process variations are particularly noticeable in premium corporate gift boxes that feature foil stamping, embossing, or specialty coatings. Foil stamping involves transferring metallic or pigmented foil onto the substrate using heat and pressure. The quality of the foil transfer depends on the temperature, pressure, dwell time, and the surface characteristics of the substrate. When a supplier creates a sample, the foil stamping operator can take time to optimise these parameters for the specific substrate being used. During production, the foil stamping machine runs at higher speeds, and the parameters are set for efficiency rather than perfection. The result is that foil coverage may be slightly less complete on production units—there may be small areas where the foil has not transferred fully, or the edges of the foil may be slightly less crisp. Embossing quality is similarly affected by production speed. A sample may feature deep, well-defined embossing with crisp edges, while production units may have slightly shallower embossing with softer edges. Specialty coatings such as soft-touch lamination, spot UV, and textured finishes are also subject to variation based on production speed, material batch, and environmental conditions during application.

The colour matching challenge is compounded by the difference between digital proofs and physical samples. When a procurement team reviews a digital proof, they are looking at a representation of the design on their computer screen or printed on their office printer. The colours they see are determined by their screen calibration, ambient lighting, and the colour profile of the proof file. When the physical sample arrives, the colours may look different because the sample is printed on actual substrate using actual inks, which behave differently than the digital simulation. The procurement team approves the sample because it looks "close enough" to the digital proof, without realising that the sample itself may not be representative of production output. When the production run arrives, the colours may be different from both the digital proof and the sample—different from the digital proof because of the inherent limitations of digital colour simulation, and different from the sample because of material batch variation and production speed effects.

The printing process differences between sample production and mass production create another layer of visual variation. When a supplier prints a sample, the press operator can take time to adjust ink density, registration, and colour balance until the output matches the design proof exactly. The press may run at 30-40% of its normal speed, which allows for more precise ink transfer and sharper image reproduction. The operator may print several test sheets and select the best one to use as the sample. During production, the press runs at full speed to meet the delivery deadline and maintain cost efficiency. The operator makes adjustments at the start of the run, but once production is underway, there is limited opportunity for fine-tuning. The first 50-100 sheets of a production run are typically considered "make-ready" sheets—sheets that are used to calibrate the press and are not included in the final shipment. The remaining sheets are printed at production speed, and while they meet the supplier's quality control standards, they may not match the sample exactly. The colours may be slightly more saturated or slightly less saturated. The registration may be slightly off on some sheets. The ink coverage may be slightly uneven in areas of heavy coverage. These variations are within industry tolerances, but they are visible when compared to the hand-selected sample.

The finishing process variations are particularly noticeable in premium corporate gift boxes that feature foil stamping, embossing, or specialty coatings. Foil stamping involves transferring metallic or pigmented foil onto the substrate using heat and pressure. The quality of the foil transfer depends on the temperature, pressure, dwell time, and the surface characteristics of the substrate. When a supplier creates a sample, the foil stamping operator can take time to optimise these parameters for the specific substrate being used. During production, the foil stamping machine runs at higher speeds, and the parameters are set for efficiency rather than perfection. The result is that foil coverage may be slightly less complete on production units—there may be small areas where the foil has not transferred fully, or the edges of the foil may be slightly less crisp. Embossing quality is similarly affected by production speed. A sample may feature deep, well-defined embossing with crisp edges, while production units may have slightly shallower embossing with softer edges. Specialty coatings such as soft-touch lamination, spot UV, and textured finishes are also subject to variation based on production speed, material batch, and environmental conditions during application.

The colour matching challenge is compounded by the difference between digital proofs and physical samples. When a procurement team reviews a digital proof, they are looking at a representation of the design on their computer screen or printed on their office printer. The colours they see are determined by their screen calibration, ambient lighting, and the colour profile of the proof file. When the physical sample arrives, the colours may look different because the sample is printed on actual substrate using actual inks, which behave differently than the digital simulation. The procurement team approves the sample because it looks "close enough" to the digital proof, without realising that the sample itself may not be representative of production output. When the production run arrives, the colours may be different from both the digital proof and the sample—different from the digital proof because of the inherent limitations of digital colour simulation, and different from the sample because of material batch variation and production speed effects.

The supplier's material substitution practices are another source of sample-to-production discrepancy that is rarely disclosed to procurement teams. When a supplier creates a sample, they may use premium materials from their inventory to showcase their best work. When the production order is placed, the supplier may substitute materials that meet the same specifications but come from different sources or have different characteristics. For example, a supplier may use virgin paper stock for the sample but mechanically recycled paper stock for production—both meet the "300gsm coated board" specification, but the recycled stock may have visible speckling or a slightly different colour tone. A supplier may use a premium soft-touch lamination film for the sample but a standard soft-touch film for production—both provide a soft-touch finish, but the premium film has a smoother, more luxurious feel. These substitutions are not necessarily deceptive—they may be driven by material availability, cost pressures, or sustainability commitments—but they result in production output that looks and feels different from the approved sample.

The environmental conditions during production can also affect the visual consistency of corporate gift boxes. Paper and board materials are hygroscopic—they absorb and release moisture based on the humidity of their environment. A sample produced in a climate-controlled facility during the dry season may have different characteristics than a production run manufactured during the humid season. The board may be slightly softer, the ink may absorb differently, and the lamination may adhere with different characteristics. These environmental effects are within normal manufacturing tolerances, but they contribute to the cumulative visual difference between samples and production output. Suppliers in the UK and Europe are particularly aware of these seasonal variations, as humidity levels can vary significantly between summer and winter months.

The quality control standards applied to samples versus production runs are fundamentally different. When a supplier creates a sample, the quality control process is essentially 100% inspection—every aspect of the sample is reviewed and verified before it is sent to the client. If the sample has any defect, it is discarded and a new sample is created. During production, quality control is based on statistical sampling—a percentage of units are inspected, and the batch is accepted or rejected based on the results of the sample inspection. The Acceptable Quality Level (AQL) for custom packaging typically allows for 2.5-4% defects in a production batch, depending on the defect severity classification. This means that a production shipment of 5,000 units may contain 125-200 units with minor defects—units that would never have been sent as samples but are acceptable within production quality standards. When the procurement team receives the shipment and inspects the units, they may find defects that were not present in the approved sample, leading to the conclusion that the supplier has failed to maintain quality standards.

The business impact of sample-to-production discrepancy extends beyond aesthetic disappointment—it can affect brand perception, recipient experience, and the success of the corporate gifting programme. When a procurement team approves a sample, they are making a commitment to their internal stakeholders about the quality of the gift boxes that will be delivered. If the production run does not match the sample, the procurement team must decide whether to accept the shipment, request rework, or reject the order entirely. Accepting a shipment that does not match the sample may damage the company's brand perception if the gift boxes are distributed to clients or employees who notice the quality difference. Requesting rework delays the delivery and may not fully resolve the quality issues. Rejecting the order creates a crisis—the corporate event is approaching, and there is no time to source alternative gift boxes. The procurement team is left with no good options, and the supplier relationship may be damaged regardless of the outcome.

When planning custom corporate gift box projects, it's essential to understand that sample approval establishes a quality benchmark, not a production guarantee. For comprehensive guidance on managing the customization process from concept through delivery—including strategies for specifying quality requirements that translate to production—refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial design through final delivery.

The practical solution for procurement teams is to establish explicit quality specifications that go beyond "match the sample." Instead of relying on sample approval as the sole quality benchmark, procurement teams should specify acceptable tolerances for colour variation (using Delta E measurements), material characteristics (including specific paper grades and sources), finishing quality (including foil coverage percentage and embossing depth), and defect rates (using AQL standards). These specifications should be included in the purchase order and agreed upon by the supplier before production begins. The procurement team should also request a pre-production sample—a sample produced using the actual materials and processes that will be used for the production run—rather than relying on a showcase sample produced under ideal conditions. This pre-production sample provides a more accurate preview of what the production output will look like and allows the procurement team to identify and address any quality concerns before the full production run is completed.

The supplier relationship management aspect of sample-to-production quality is often overlooked by procurement teams. Suppliers are not trying to deceive their clients by producing samples that exceed production quality—they are trying to win the business by showcasing their best work. The disconnect between sample quality and production quality is a structural feature of the custom packaging industry, not a failure of individual suppliers. Procurement teams who understand this dynamic can work more effectively with their suppliers by setting realistic expectations, specifying explicit quality requirements, and building quality verification checkpoints into the production process. By treating sample approval as the beginning of a quality management process rather than the end, procurement teams can reduce the risk of sample-to-production discrepancy and ensure that the final delivery meets their expectations.

The documentation and communication practices around sample approval are critical to managing expectations. When a procurement team approves a sample, they should document exactly what they are approving—the colour, the material feel, the finishing quality, the structural integrity—and communicate these expectations to the supplier in writing. The supplier should confirm that these characteristics can be maintained at production scale, or disclose any expected variations. This documentation creates a shared understanding of quality expectations and provides a reference point for quality disputes if they arise. Without explicit documentation, the procurement team's expectations are based on their subjective interpretation of the sample, and the supplier's commitments are based on their standard production capabilities. The gap between these interpretations is where quality disputes originate.

The timeline implications of sample-to-production quality management are significant. If a procurement team wants to verify production quality before the full shipment is delivered, they need to build time into the project schedule for pre-production samples, quality review, and potential adjustments. A pre-production sample typically adds 1-2 weeks to the project timeline—time for the supplier to source production materials, produce a sample using production processes, ship the sample to the client, and receive approval. If the pre-production sample reveals quality issues, additional time is needed for the supplier to make adjustments and produce a revised sample. Procurement teams who do not build this time into their project schedules are forced to accept production output without verification, which increases the risk of quality disappointment. The choice is between investing time upfront in quality verification or accepting the risk of quality issues at delivery.

The cost implications of sample-to-production quality management should also be considered. Pre-production samples, explicit quality specifications, and quality verification checkpoints all add cost to the project—cost that may be absorbed by the supplier, passed on to the buyer, or shared between both parties. Procurement teams should discuss these costs with their suppliers during the quotation process and make informed decisions about the level of quality assurance they require. For high-visibility corporate gifting programmes where brand perception is critical, the additional cost of quality verification is a worthwhile investment. For lower-stakes projects where minor quality variations are acceptable, the standard sample approval process may be sufficient. The key is to make this decision consciously, based on a clear understanding of the risks and trade-offs, rather than assuming that sample approval guarantees production quality.

The supplier's material substitution practices are another source of sample-to-production discrepancy that is rarely disclosed to procurement teams. When a supplier creates a sample, they may use premium materials from their inventory to showcase their best work. When the production order is placed, the supplier may substitute materials that meet the same specifications but come from different sources or have different characteristics. For example, a supplier may use virgin paper stock for the sample but mechanically recycled paper stock for production—both meet the "300gsm coated board" specification, but the recycled stock may have visible speckling or a slightly different colour tone. A supplier may use a premium soft-touch lamination film for the sample but a standard soft-touch film for production—both provide a soft-touch finish, but the premium film has a smoother, more luxurious feel. These substitutions are not necessarily deceptive—they may be driven by material availability, cost pressures, or sustainability commitments—but they result in production output that looks and feels different from the approved sample.

The environmental conditions during production can also affect the visual consistency of corporate gift boxes. Paper and board materials are hygroscopic—they absorb and release moisture based on the humidity of their environment. A sample produced in a climate-controlled facility during the dry season may have different characteristics than a production run manufactured during the humid season. The board may be slightly softer, the ink may absorb differently, and the lamination may adhere with different characteristics. These environmental effects are within normal manufacturing tolerances, but they contribute to the cumulative visual difference between samples and production output. Suppliers in the UK and Europe are particularly aware of these seasonal variations, as humidity levels can vary significantly between summer and winter months.

The quality control standards applied to samples versus production runs are fundamentally different. When a supplier creates a sample, the quality control process is essentially 100% inspection—every aspect of the sample is reviewed and verified before it is sent to the client. If the sample has any defect, it is discarded and a new sample is created. During production, quality control is based on statistical sampling—a percentage of units are inspected, and the batch is accepted or rejected based on the results of the sample inspection. The Acceptable Quality Level (AQL) for custom packaging typically allows for 2.5-4% defects in a production batch, depending on the defect severity classification. This means that a production shipment of 5,000 units may contain 125-200 units with minor defects—units that would never have been sent as samples but are acceptable within production quality standards. When the procurement team receives the shipment and inspects the units, they may find defects that were not present in the approved sample, leading to the conclusion that the supplier has failed to maintain quality standards.

The business impact of sample-to-production discrepancy extends beyond aesthetic disappointment—it can affect brand perception, recipient experience, and the success of the corporate gifting programme. When a procurement team approves a sample, they are making a commitment to their internal stakeholders about the quality of the gift boxes that will be delivered. If the production run does not match the sample, the procurement team must decide whether to accept the shipment, request rework, or reject the order entirely. Accepting a shipment that does not match the sample may damage the company's brand perception if the gift boxes are distributed to clients or employees who notice the quality difference. Requesting rework delays the delivery and may not fully resolve the quality issues. Rejecting the order creates a crisis—the corporate event is approaching, and there is no time to source alternative gift boxes. The procurement team is left with no good options, and the supplier relationship may be damaged regardless of the outcome.

When planning custom corporate gift box projects, it's essential to understand that sample approval establishes a quality benchmark, not a production guarantee. For comprehensive guidance on managing the customization process from concept through delivery—including strategies for specifying quality requirements that translate to production—refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial design through final delivery.

The practical solution for procurement teams is to establish explicit quality specifications that go beyond "match the sample." Instead of relying on sample approval as the sole quality benchmark, procurement teams should specify acceptable tolerances for colour variation (using Delta E measurements), material characteristics (including specific paper grades and sources), finishing quality (including foil coverage percentage and embossing depth), and defect rates (using AQL standards). These specifications should be included in the purchase order and agreed upon by the supplier before production begins. The procurement team should also request a pre-production sample—a sample produced using the actual materials and processes that will be used for the production run—rather than relying on a showcase sample produced under ideal conditions. This pre-production sample provides a more accurate preview of what the production output will look like and allows the procurement team to identify and address any quality concerns before the full production run is completed.

The supplier relationship management aspect of sample-to-production quality is often overlooked by procurement teams. Suppliers are not trying to deceive their clients by producing samples that exceed production quality—they are trying to win the business by showcasing their best work. The disconnect between sample quality and production quality is a structural feature of the custom packaging industry, not a failure of individual suppliers. Procurement teams who understand this dynamic can work more effectively with their suppliers by setting realistic expectations, specifying explicit quality requirements, and building quality verification checkpoints into the production process. By treating sample approval as the beginning of a quality management process rather than the end, procurement teams can reduce the risk of sample-to-production discrepancy and ensure that the final delivery meets their expectations.

The documentation and communication practices around sample approval are critical to managing expectations. When a procurement team approves a sample, they should document exactly what they are approving—the colour, the material feel, the finishing quality, the structural integrity—and communicate these expectations to the supplier in writing. The supplier should confirm that these characteristics can be maintained at production scale, or disclose any expected variations. This documentation creates a shared understanding of quality expectations and provides a reference point for quality disputes if they arise. Without explicit documentation, the procurement team's expectations are based on their subjective interpretation of the sample, and the supplier's commitments are based on their standard production capabilities. The gap between these interpretations is where quality disputes originate.

The timeline implications of sample-to-production quality management are significant. If a procurement team wants to verify production quality before the full shipment is delivered, they need to build time into the project schedule for pre-production samples, quality review, and potential adjustments. A pre-production sample typically adds 1-2 weeks to the project timeline—time for the supplier to source production materials, produce a sample using production processes, ship the sample to the client, and receive approval. If the pre-production sample reveals quality issues, additional time is needed for the supplier to make adjustments and produce a revised sample. Procurement teams who do not build this time into their project schedules are forced to accept production output without verification, which increases the risk of quality disappointment. The choice is between investing time upfront in quality verification or accepting the risk of quality issues at delivery.

The cost implications of sample-to-production quality management should also be considered. Pre-production samples, explicit quality specifications, and quality verification checkpoints all add cost to the project—cost that may be absorbed by the supplier, passed on to the buyer, or shared between both parties. Procurement teams should discuss these costs with their suppliers during the quotation process and make informed decisions about the level of quality assurance they require. For high-visibility corporate gifting programmes where brand perception is critical, the additional cost of quality verification is a worthwhile investment. For lower-stakes projects where minor quality variations are acceptable, the standard sample approval process may be sufficient. The key is to make this decision consciously, based on a clear understanding of the risks and trade-offs, rather than assuming that sample approval guarantees production quality.

You May Also Like

Rigid Box vs. Corrugated Mailer: Which Material Suits Your Premium Corporate Gifts?

A deep dive into the structural integrity, cost implications, and unboxing experience of rigid boxes versus corrugated mailers for high-end corporate gifting.

Foil Stamping vs. UV Spot: Elevating Your Brand Logo on Custom Gift Boxes

A technical comparison of hot foil stamping and UV spot varnish, analyzing visual impact, durability, and production costs for branded corporate packaging.