Back to BlogCustomization Process

Why Your Packaging Supplier's MOQ Isn't Negotiable Like You Think

2026-01-29

When a procurement manager receives a quote for custom corporate gift boxes with a minimum order quantity of 1,000 units but only needs 300, the instinctive response is to negotiate. The manager contacts the supplier and offers to pay 20% more per unit if the supplier will accept an order of 300 units instead. The supplier declines. The manager increases the offer to 30% more per unit. The supplier declines again. The manager concludes that the supplier is inflexible or that the MOQ is artificially inflated to maximize revenue. In practice, the supplier's MOQ is not a negotiation starting point—it's a hard floor determined by the fixed cost structure of custom packaging production. The misjudgment occurs because procurement teams treat MOQ as if it were analogous to unit pricing, when in reality it reflects the minimum production volume at which the supplier can recover their non-negotiable setup costs without operating at a loss.

The fundamental difference between pricing negotiation and MOQ negotiation lies in the cost structure being optimized. When a procurement team negotiates unit pricing, they are negotiating the supplier's profit margin on variable costs—materials, labor, and overhead that scale proportionally with order volume. A supplier can reduce their unit price by accepting a lower profit margin, and this reduction is sustainable as long as the price remains above their variable cost floor. When a procurement team attempts to negotiate MOQ, they are not negotiating profit margin—they are negotiating whether the supplier will absorb a fixed cost loss. The supplier's MOQ is set at the volume where the per-unit contribution from the order is sufficient to cover the fixed costs of production setup. Below that volume, the supplier operates at a loss on the order, regardless of how much the buyer offers to pay per unit. Offering to pay 20% or 30% more per unit does not change this equation if the order volume is too small to amortize the fixed costs.

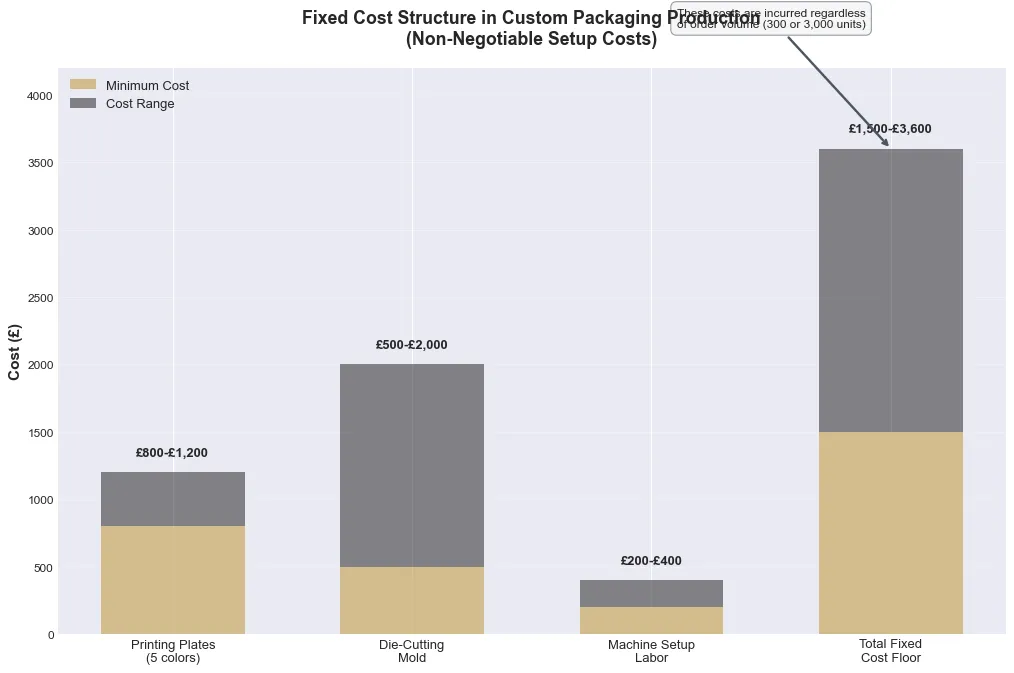

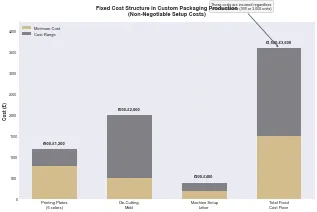

The fixed cost structure of custom packaging production is dominated by three non-negotiable expenses: printing plate creation, die-cutting mold fabrication, and machine setup labor. For a custom corporate gift box with a four-color logo printed on the exterior, the supplier must create four separate printing plates—one for each color in the CMYK process. If the design includes a Pantone spot color for brand consistency, that's a fifth plate. Each plate costs the supplier several hundred pounds to produce, and this cost is incurred regardless of whether the supplier prints 300 boxes or 3,000 boxes. The total plate cost for a five-color design might be £800-1,200. If the box has a custom shape or size that requires a die-cutting mold, that mold must be fabricated by a specialist tooling shop. The cost of creating a custom die ranges from £500 to £2,000, depending on the complexity of the box structure. This cost is also incurred regardless of order volume. The machine setup labor—the time required to stop the printing press, clean it, mount the new plates, load the correct paper stock, mix the inks, and calibrate the registration—takes 2-4 hours and costs the supplier £200-400 in labor. These three fixed costs—plates, die, and setup labor—total £1,500-3,600 for a typical custom corporate gift box project. This is the fixed cost floor that the supplier must recover from the order.

The arithmetic of fixed cost recovery explains why offering to pay more per unit does not unlock lower MOQs. Assume the supplier's variable cost (materials + labor + overhead) for each box is £3.00, and the supplier's standard unit price at 1,000 units is £4.50. The supplier's contribution margin is £1.50 per unit, which means the supplier recovers £1,500 in contribution from a 1,000-unit order. This £1,500 contribution must cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a profit margin of £0 to -£2,100 depending on the complexity of the job. At 1,000 units, the supplier breaks even or operates at a small loss, which they accept because the order keeps their production line running and builds a customer relationship. Now assume the procurement manager offers to pay £5.40 per unit (20% more) for an order of 300 units. The supplier's contribution margin increases to £2.40 per unit, and the total contribution from the order is £720. This £720 contribution is insufficient to cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a loss of £780-2,880 on the order. Offering to pay 30% more per unit (£5.85) increases the contribution to £855, but the supplier still operates at a loss of £645-2,745. The supplier cannot accept this order without subsidizing the buyer's project with their own capital.

The material sourcing constraint adds another layer of inflexibility to the MOQ equation. Packaging suppliers do not manufacture paper or cardboard—they purchase it in bulk from paper mills. Paper mills operate massive production machinery that requires long, uninterrupted runs to be economically viable, and they impose their own MOQs on their customers. A paper mill might require a minimum order of 5 tons for a standard white coated cardboard, or 10 tons for a custom-dyed color. If a procurement team requests custom corporate gift boxes made from a specific shade of green cardboard that the supplier does not normally stock, the supplier must place a special order with the paper mill. The paper mill's MOQ might be 10 tons, which is enough material to produce 50,000 boxes. The supplier is now faced with a choice: order 10 tons of green cardboard to fulfill a 300-unit order, leaving them with 9.94 tons of unsellable inventory, or decline the order. The supplier cannot pass the cost of 10 tons of cardboard onto a 300-unit order without making the per-unit price prohibitively expensive. The supplier also cannot justify ordering 10 tons of a non-standard material for a one-time project. The material sourcing constraint is non-negotiable, and it sets a hard floor on the MOQ for any project that requires non-standard materials.

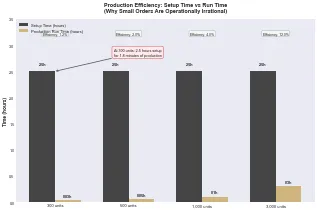

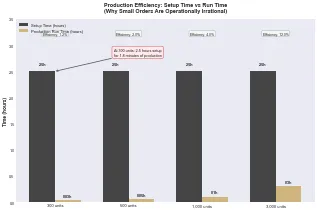

The operational efficiency mandate reinforces the MOQ floor from a different angle. Packaging factories operate multi-million-pound printing presses that are designed to run at high speeds for long, uninterrupted periods. A typical press can print 10,000 impressions per hour. A 1,000-unit order runs for 6 minutes. A 300-unit order runs for 1.8 minutes. The setup time for both orders is 2-4 hours. From the factory's perspective, a 300-unit order consumes 2-4 hours of setup time to produce 1.8 minutes of output. This is operationally inefficient to the point of being economically irrational. The factory's profitability depends on maximizing the ratio of production time to setup time. A 1,000-unit order achieves a 6-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is still inefficient but tolerable. A 300-unit order achieves a 1.8-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is intolerable. The factory's MOQ is set at the minimum volume where the production time justifies the setup time. Below that volume, the factory is better off leaving the press idle than running a job that generates negligible output for significant setup investment.

The arithmetic of fixed cost recovery explains why offering to pay more per unit does not unlock lower MOQs. Assume the supplier's variable cost (materials + labor + overhead) for each box is £3.00, and the supplier's standard unit price at 1,000 units is £4.50. The supplier's contribution margin is £1.50 per unit, which means the supplier recovers £1,500 in contribution from a 1,000-unit order. This £1,500 contribution must cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a profit margin of £0 to -£2,100 depending on the complexity of the job. At 1,000 units, the supplier breaks even or operates at a small loss, which they accept because the order keeps their production line running and builds a customer relationship. Now assume the procurement manager offers to pay £5.40 per unit (20% more) for an order of 300 units. The supplier's contribution margin increases to £2.40 per unit, and the total contribution from the order is £720. This £720 contribution is insufficient to cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a loss of £780-2,880 on the order. Offering to pay 30% more per unit (£5.85) increases the contribution to £855, but the supplier still operates at a loss of £645-2,745. The supplier cannot accept this order without subsidizing the buyer's project with their own capital.

The material sourcing constraint adds another layer of inflexibility to the MOQ equation. Packaging suppliers do not manufacture paper or cardboard—they purchase it in bulk from paper mills. Paper mills operate massive production machinery that requires long, uninterrupted runs to be economically viable, and they impose their own MOQs on their customers. A paper mill might require a minimum order of 5 tons for a standard white coated cardboard, or 10 tons for a custom-dyed color. If a procurement team requests custom corporate gift boxes made from a specific shade of green cardboard that the supplier does not normally stock, the supplier must place a special order with the paper mill. The paper mill's MOQ might be 10 tons, which is enough material to produce 50,000 boxes. The supplier is now faced with a choice: order 10 tons of green cardboard to fulfill a 300-unit order, leaving them with 9.94 tons of unsellable inventory, or decline the order. The supplier cannot pass the cost of 10 tons of cardboard onto a 300-unit order without making the per-unit price prohibitively expensive. The supplier also cannot justify ordering 10 tons of a non-standard material for a one-time project. The material sourcing constraint is non-negotiable, and it sets a hard floor on the MOQ for any project that requires non-standard materials.

The operational efficiency mandate reinforces the MOQ floor from a different angle. Packaging factories operate multi-million-pound printing presses that are designed to run at high speeds for long, uninterrupted periods. A typical press can print 10,000 impressions per hour. A 1,000-unit order runs for 6 minutes. A 300-unit order runs for 1.8 minutes. The setup time for both orders is 2-4 hours. From the factory's perspective, a 300-unit order consumes 2-4 hours of setup time to produce 1.8 minutes of output. This is operationally inefficient to the point of being economically irrational. The factory's profitability depends on maximizing the ratio of production time to setup time. A 1,000-unit order achieves a 6-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is still inefficient but tolerable. A 300-unit order achieves a 1.8-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is intolerable. The factory's MOQ is set at the minimum volume where the production time justifies the setup time. Below that volume, the factory is better off leaving the press idle than running a job that generates negligible output for significant setup investment.

The misjudgment that MOQ is negotiable like pricing stems from a lack of visibility into the supplier's cost structure. Procurement teams see the unit price and the MOQ as two variables in the same negotiation. They assume that if they offer to increase one variable (unit price), the supplier should be willing to decrease the other variable (MOQ). This assumption is valid when both variables affect the same cost component—profit margin. It is invalid when the variables affect different cost components—one affects variable costs (unit price) and the other affects fixed costs (MOQ). The supplier's MOQ is not a profit maximization strategy—it's a loss prevention strategy. The supplier is not trying to extract maximum revenue from the buyer by imposing a high MOQ. The supplier is trying to avoid operating at a loss by setting the MOQ at the minimum volume where fixed costs can be recovered.

The practical implication for procurement teams is that MOQ negotiation requires a different strategy than pricing negotiation. Instead of offering to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, procurement teams should focus on strategies that reduce the supplier's fixed costs or increase the supplier's production efficiency. One approach is to simplify the design to reduce the number of printing plates required. A four-color CMYK design requires four plates. A two-color design requires two plates, reducing the fixed cost by £400-600. A one-color design requires one plate, reducing the fixed cost by £600-900. By simplifying the design, the procurement team reduces the supplier's fixed cost floor, which allows the supplier to lower the MOQ without operating at a loss. Another approach is to select a standard box size that does not require a custom die. If the supplier already has a die for a standard box size, the die cost is eliminated, reducing the fixed cost by £500-2,000. This reduction in fixed costs allows the supplier to lower the MOQ significantly.

A third approach is to commit to a long-term relationship with the supplier that justifies the supplier's investment in custom tooling. If a procurement team places a 300-unit order but commits to placing additional orders over the next 12 months, the supplier can amortize the fixed tooling costs across multiple orders. The supplier might accept a 300-unit initial order at a higher per-unit price, with the understanding that the tooling investment will be recovered over subsequent orders. This approach transforms the MOQ negotiation from a single-transaction discussion into a relationship-building discussion. The supplier is more willing to absorb a short-term loss on the initial order if they have confidence that the relationship will generate long-term profitability.

When evaluating custom corporate gift box projects with varying quantity requirements, it's essential to understand how design complexity, material selection, and production constraints interact to determine feasibility. For comprehensive guidance on structuring projects that balance customization ambitions with quantity economics, refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial concept through final delivery and helps procurement teams make informed decisions about when full customization is appropriate versus when modified approaches might deliver better value.

The fourth approach is to explore alternative suppliers whose production capabilities align better with the buyer's order volume. Not all packaging suppliers operate the same equipment or have the same cost structure. A large-scale supplier with high-speed presses and complex tooling might have an MOQ of 1,000-5,000 units. A smaller-scale supplier with digital printing equipment might have an MOQ of 100-500 units. Digital printing eliminates the need for printing plates, which removes a significant fixed cost component. The trade-off is that digital printing is more expensive per unit than offset or flexographic printing, so the unit price at 300 units might be higher than the unit price at 1,000 units from a large-scale supplier. The procurement team must decide whether the lower MOQ justifies the higher unit price. This decision depends on the buyer's storage capacity, cash flow constraints, and demand certainty. If the buyer cannot store 1,000 units or cannot afford the upfront capital outlay, the higher per-unit cost of a 300-unit order from a digital printing supplier might be the more economical choice.

The supplier's perspective on MOQ is fundamentally protective, not opportunistic. Suppliers set MOQs to ensure that each order generates enough contribution to cover fixed costs and maintain operational efficiency. They are not trying to force buyers to order more than they need—they are trying to avoid accepting orders that will cause them to operate at a loss. When a procurement team offers to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, the supplier runs the arithmetic and determines whether the increased contribution is sufficient to cover the fixed costs. In most cases, it is not. The supplier declines the order not because they are inflexible, but because accepting the order would be economically irrational. By understanding the supplier's cost structure and focusing on strategies that reduce fixed costs or increase production efficiency, procurement teams can have more productive MOQ discussions that result in mutually beneficial outcomes rather than adversarial negotiations that end in stalemate.

The misjudgment that MOQ is negotiable like pricing stems from a lack of visibility into the supplier's cost structure. Procurement teams see the unit price and the MOQ as two variables in the same negotiation. They assume that if they offer to increase one variable (unit price), the supplier should be willing to decrease the other variable (MOQ). This assumption is valid when both variables affect the same cost component—profit margin. It is invalid when the variables affect different cost components—one affects variable costs (unit price) and the other affects fixed costs (MOQ). The supplier's MOQ is not a profit maximization strategy—it's a loss prevention strategy. The supplier is not trying to extract maximum revenue from the buyer by imposing a high MOQ. The supplier is trying to avoid operating at a loss by setting the MOQ at the minimum volume where fixed costs can be recovered.

The practical implication for procurement teams is that MOQ negotiation requires a different strategy than pricing negotiation. Instead of offering to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, procurement teams should focus on strategies that reduce the supplier's fixed costs or increase the supplier's production efficiency. One approach is to simplify the design to reduce the number of printing plates required. A four-color CMYK design requires four plates. A two-color design requires two plates, reducing the fixed cost by £400-600. A one-color design requires one plate, reducing the fixed cost by £600-900. By simplifying the design, the procurement team reduces the supplier's fixed cost floor, which allows the supplier to lower the MOQ without operating at a loss. Another approach is to select a standard box size that does not require a custom die. If the supplier already has a die for a standard box size, the die cost is eliminated, reducing the fixed cost by £500-2,000. This reduction in fixed costs allows the supplier to lower the MOQ significantly.

A third approach is to commit to a long-term relationship with the supplier that justifies the supplier's investment in custom tooling. If a procurement team places a 300-unit order but commits to placing additional orders over the next 12 months, the supplier can amortize the fixed tooling costs across multiple orders. The supplier might accept a 300-unit initial order at a higher per-unit price, with the understanding that the tooling investment will be recovered over subsequent orders. This approach transforms the MOQ negotiation from a single-transaction discussion into a relationship-building discussion. The supplier is more willing to absorb a short-term loss on the initial order if they have confidence that the relationship will generate long-term profitability.

When evaluating custom corporate gift box projects with varying quantity requirements, it's essential to understand how design complexity, material selection, and production constraints interact to determine feasibility. For comprehensive guidance on structuring projects that balance customization ambitions with quantity economics, refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial concept through final delivery and helps procurement teams make informed decisions about when full customization is appropriate versus when modified approaches might deliver better value.

The fourth approach is to explore alternative suppliers whose production capabilities align better with the buyer's order volume. Not all packaging suppliers operate the same equipment or have the same cost structure. A large-scale supplier with high-speed presses and complex tooling might have an MOQ of 1,000-5,000 units. A smaller-scale supplier with digital printing equipment might have an MOQ of 100-500 units. Digital printing eliminates the need for printing plates, which removes a significant fixed cost component. The trade-off is that digital printing is more expensive per unit than offset or flexographic printing, so the unit price at 300 units might be higher than the unit price at 1,000 units from a large-scale supplier. The procurement team must decide whether the lower MOQ justifies the higher unit price. This decision depends on the buyer's storage capacity, cash flow constraints, and demand certainty. If the buyer cannot store 1,000 units or cannot afford the upfront capital outlay, the higher per-unit cost of a 300-unit order from a digital printing supplier might be the more economical choice.

The supplier's perspective on MOQ is fundamentally protective, not opportunistic. Suppliers set MOQs to ensure that each order generates enough contribution to cover fixed costs and maintain operational efficiency. They are not trying to force buyers to order more than they need—they are trying to avoid accepting orders that will cause them to operate at a loss. When a procurement team offers to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, the supplier runs the arithmetic and determines whether the increased contribution is sufficient to cover the fixed costs. In most cases, it is not. The supplier declines the order not because they are inflexible, but because accepting the order would be economically irrational. By understanding the supplier's cost structure and focusing on strategies that reduce fixed costs or increase production efficiency, procurement teams can have more productive MOQ discussions that result in mutually beneficial outcomes rather than adversarial negotiations that end in stalemate.

The arithmetic of fixed cost recovery explains why offering to pay more per unit does not unlock lower MOQs. Assume the supplier's variable cost (materials + labor + overhead) for each box is £3.00, and the supplier's standard unit price at 1,000 units is £4.50. The supplier's contribution margin is £1.50 per unit, which means the supplier recovers £1,500 in contribution from a 1,000-unit order. This £1,500 contribution must cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a profit margin of £0 to -£2,100 depending on the complexity of the job. At 1,000 units, the supplier breaks even or operates at a small loss, which they accept because the order keeps their production line running and builds a customer relationship. Now assume the procurement manager offers to pay £5.40 per unit (20% more) for an order of 300 units. The supplier's contribution margin increases to £2.40 per unit, and the total contribution from the order is £720. This £720 contribution is insufficient to cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a loss of £780-2,880 on the order. Offering to pay 30% more per unit (£5.85) increases the contribution to £855, but the supplier still operates at a loss of £645-2,745. The supplier cannot accept this order without subsidizing the buyer's project with their own capital.

The material sourcing constraint adds another layer of inflexibility to the MOQ equation. Packaging suppliers do not manufacture paper or cardboard—they purchase it in bulk from paper mills. Paper mills operate massive production machinery that requires long, uninterrupted runs to be economically viable, and they impose their own MOQs on their customers. A paper mill might require a minimum order of 5 tons for a standard white coated cardboard, or 10 tons for a custom-dyed color. If a procurement team requests custom corporate gift boxes made from a specific shade of green cardboard that the supplier does not normally stock, the supplier must place a special order with the paper mill. The paper mill's MOQ might be 10 tons, which is enough material to produce 50,000 boxes. The supplier is now faced with a choice: order 10 tons of green cardboard to fulfill a 300-unit order, leaving them with 9.94 tons of unsellable inventory, or decline the order. The supplier cannot pass the cost of 10 tons of cardboard onto a 300-unit order without making the per-unit price prohibitively expensive. The supplier also cannot justify ordering 10 tons of a non-standard material for a one-time project. The material sourcing constraint is non-negotiable, and it sets a hard floor on the MOQ for any project that requires non-standard materials.

The operational efficiency mandate reinforces the MOQ floor from a different angle. Packaging factories operate multi-million-pound printing presses that are designed to run at high speeds for long, uninterrupted periods. A typical press can print 10,000 impressions per hour. A 1,000-unit order runs for 6 minutes. A 300-unit order runs for 1.8 minutes. The setup time for both orders is 2-4 hours. From the factory's perspective, a 300-unit order consumes 2-4 hours of setup time to produce 1.8 minutes of output. This is operationally inefficient to the point of being economically irrational. The factory's profitability depends on maximizing the ratio of production time to setup time. A 1,000-unit order achieves a 6-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is still inefficient but tolerable. A 300-unit order achieves a 1.8-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is intolerable. The factory's MOQ is set at the minimum volume where the production time justifies the setup time. Below that volume, the factory is better off leaving the press idle than running a job that generates negligible output for significant setup investment.

The arithmetic of fixed cost recovery explains why offering to pay more per unit does not unlock lower MOQs. Assume the supplier's variable cost (materials + labor + overhead) for each box is £3.00, and the supplier's standard unit price at 1,000 units is £4.50. The supplier's contribution margin is £1.50 per unit, which means the supplier recovers £1,500 in contribution from a 1,000-unit order. This £1,500 contribution must cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a profit margin of £0 to -£2,100 depending on the complexity of the job. At 1,000 units, the supplier breaks even or operates at a small loss, which they accept because the order keeps their production line running and builds a customer relationship. Now assume the procurement manager offers to pay £5.40 per unit (20% more) for an order of 300 units. The supplier's contribution margin increases to £2.40 per unit, and the total contribution from the order is £720. This £720 contribution is insufficient to cover the £1,500-3,600 in fixed costs, leaving the supplier with a loss of £780-2,880 on the order. Offering to pay 30% more per unit (£5.85) increases the contribution to £855, but the supplier still operates at a loss of £645-2,745. The supplier cannot accept this order without subsidizing the buyer's project with their own capital.

The material sourcing constraint adds another layer of inflexibility to the MOQ equation. Packaging suppliers do not manufacture paper or cardboard—they purchase it in bulk from paper mills. Paper mills operate massive production machinery that requires long, uninterrupted runs to be economically viable, and they impose their own MOQs on their customers. A paper mill might require a minimum order of 5 tons for a standard white coated cardboard, or 10 tons for a custom-dyed color. If a procurement team requests custom corporate gift boxes made from a specific shade of green cardboard that the supplier does not normally stock, the supplier must place a special order with the paper mill. The paper mill's MOQ might be 10 tons, which is enough material to produce 50,000 boxes. The supplier is now faced with a choice: order 10 tons of green cardboard to fulfill a 300-unit order, leaving them with 9.94 tons of unsellable inventory, or decline the order. The supplier cannot pass the cost of 10 tons of cardboard onto a 300-unit order without making the per-unit price prohibitively expensive. The supplier also cannot justify ordering 10 tons of a non-standard material for a one-time project. The material sourcing constraint is non-negotiable, and it sets a hard floor on the MOQ for any project that requires non-standard materials.

The operational efficiency mandate reinforces the MOQ floor from a different angle. Packaging factories operate multi-million-pound printing presses that are designed to run at high speeds for long, uninterrupted periods. A typical press can print 10,000 impressions per hour. A 1,000-unit order runs for 6 minutes. A 300-unit order runs for 1.8 minutes. The setup time for both orders is 2-4 hours. From the factory's perspective, a 300-unit order consumes 2-4 hours of setup time to produce 1.8 minutes of output. This is operationally inefficient to the point of being economically irrational. The factory's profitability depends on maximizing the ratio of production time to setup time. A 1,000-unit order achieves a 6-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is still inefficient but tolerable. A 300-unit order achieves a 1.8-minute production time for 2-4 hours of setup, which is intolerable. The factory's MOQ is set at the minimum volume where the production time justifies the setup time. Below that volume, the factory is better off leaving the press idle than running a job that generates negligible output for significant setup investment.

The misjudgment that MOQ is negotiable like pricing stems from a lack of visibility into the supplier's cost structure. Procurement teams see the unit price and the MOQ as two variables in the same negotiation. They assume that if they offer to increase one variable (unit price), the supplier should be willing to decrease the other variable (MOQ). This assumption is valid when both variables affect the same cost component—profit margin. It is invalid when the variables affect different cost components—one affects variable costs (unit price) and the other affects fixed costs (MOQ). The supplier's MOQ is not a profit maximization strategy—it's a loss prevention strategy. The supplier is not trying to extract maximum revenue from the buyer by imposing a high MOQ. The supplier is trying to avoid operating at a loss by setting the MOQ at the minimum volume where fixed costs can be recovered.

The practical implication for procurement teams is that MOQ negotiation requires a different strategy than pricing negotiation. Instead of offering to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, procurement teams should focus on strategies that reduce the supplier's fixed costs or increase the supplier's production efficiency. One approach is to simplify the design to reduce the number of printing plates required. A four-color CMYK design requires four plates. A two-color design requires two plates, reducing the fixed cost by £400-600. A one-color design requires one plate, reducing the fixed cost by £600-900. By simplifying the design, the procurement team reduces the supplier's fixed cost floor, which allows the supplier to lower the MOQ without operating at a loss. Another approach is to select a standard box size that does not require a custom die. If the supplier already has a die for a standard box size, the die cost is eliminated, reducing the fixed cost by £500-2,000. This reduction in fixed costs allows the supplier to lower the MOQ significantly.

A third approach is to commit to a long-term relationship with the supplier that justifies the supplier's investment in custom tooling. If a procurement team places a 300-unit order but commits to placing additional orders over the next 12 months, the supplier can amortize the fixed tooling costs across multiple orders. The supplier might accept a 300-unit initial order at a higher per-unit price, with the understanding that the tooling investment will be recovered over subsequent orders. This approach transforms the MOQ negotiation from a single-transaction discussion into a relationship-building discussion. The supplier is more willing to absorb a short-term loss on the initial order if they have confidence that the relationship will generate long-term profitability.

When evaluating custom corporate gift box projects with varying quantity requirements, it's essential to understand how design complexity, material selection, and production constraints interact to determine feasibility. For comprehensive guidance on structuring projects that balance customization ambitions with quantity economics, refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial concept through final delivery and helps procurement teams make informed decisions about when full customization is appropriate versus when modified approaches might deliver better value.

The fourth approach is to explore alternative suppliers whose production capabilities align better with the buyer's order volume. Not all packaging suppliers operate the same equipment or have the same cost structure. A large-scale supplier with high-speed presses and complex tooling might have an MOQ of 1,000-5,000 units. A smaller-scale supplier with digital printing equipment might have an MOQ of 100-500 units. Digital printing eliminates the need for printing plates, which removes a significant fixed cost component. The trade-off is that digital printing is more expensive per unit than offset or flexographic printing, so the unit price at 300 units might be higher than the unit price at 1,000 units from a large-scale supplier. The procurement team must decide whether the lower MOQ justifies the higher unit price. This decision depends on the buyer's storage capacity, cash flow constraints, and demand certainty. If the buyer cannot store 1,000 units or cannot afford the upfront capital outlay, the higher per-unit cost of a 300-unit order from a digital printing supplier might be the more economical choice.

The supplier's perspective on MOQ is fundamentally protective, not opportunistic. Suppliers set MOQs to ensure that each order generates enough contribution to cover fixed costs and maintain operational efficiency. They are not trying to force buyers to order more than they need—they are trying to avoid accepting orders that will cause them to operate at a loss. When a procurement team offers to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, the supplier runs the arithmetic and determines whether the increased contribution is sufficient to cover the fixed costs. In most cases, it is not. The supplier declines the order not because they are inflexible, but because accepting the order would be economically irrational. By understanding the supplier's cost structure and focusing on strategies that reduce fixed costs or increase production efficiency, procurement teams can have more productive MOQ discussions that result in mutually beneficial outcomes rather than adversarial negotiations that end in stalemate.

The misjudgment that MOQ is negotiable like pricing stems from a lack of visibility into the supplier's cost structure. Procurement teams see the unit price and the MOQ as two variables in the same negotiation. They assume that if they offer to increase one variable (unit price), the supplier should be willing to decrease the other variable (MOQ). This assumption is valid when both variables affect the same cost component—profit margin. It is invalid when the variables affect different cost components—one affects variable costs (unit price) and the other affects fixed costs (MOQ). The supplier's MOQ is not a profit maximization strategy—it's a loss prevention strategy. The supplier is not trying to extract maximum revenue from the buyer by imposing a high MOQ. The supplier is trying to avoid operating at a loss by setting the MOQ at the minimum volume where fixed costs can be recovered.

The practical implication for procurement teams is that MOQ negotiation requires a different strategy than pricing negotiation. Instead of offering to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, procurement teams should focus on strategies that reduce the supplier's fixed costs or increase the supplier's production efficiency. One approach is to simplify the design to reduce the number of printing plates required. A four-color CMYK design requires four plates. A two-color design requires two plates, reducing the fixed cost by £400-600. A one-color design requires one plate, reducing the fixed cost by £600-900. By simplifying the design, the procurement team reduces the supplier's fixed cost floor, which allows the supplier to lower the MOQ without operating at a loss. Another approach is to select a standard box size that does not require a custom die. If the supplier already has a die for a standard box size, the die cost is eliminated, reducing the fixed cost by £500-2,000. This reduction in fixed costs allows the supplier to lower the MOQ significantly.

A third approach is to commit to a long-term relationship with the supplier that justifies the supplier's investment in custom tooling. If a procurement team places a 300-unit order but commits to placing additional orders over the next 12 months, the supplier can amortize the fixed tooling costs across multiple orders. The supplier might accept a 300-unit initial order at a higher per-unit price, with the understanding that the tooling investment will be recovered over subsequent orders. This approach transforms the MOQ negotiation from a single-transaction discussion into a relationship-building discussion. The supplier is more willing to absorb a short-term loss on the initial order if they have confidence that the relationship will generate long-term profitability.

When evaluating custom corporate gift box projects with varying quantity requirements, it's essential to understand how design complexity, material selection, and production constraints interact to determine feasibility. For comprehensive guidance on structuring projects that balance customization ambitions with quantity economics, refer to our [detailed guide on customization planning](/resources/customization-process-guide), which addresses the complete journey from initial concept through final delivery and helps procurement teams make informed decisions about when full customization is appropriate versus when modified approaches might deliver better value.

The fourth approach is to explore alternative suppliers whose production capabilities align better with the buyer's order volume. Not all packaging suppliers operate the same equipment or have the same cost structure. A large-scale supplier with high-speed presses and complex tooling might have an MOQ of 1,000-5,000 units. A smaller-scale supplier with digital printing equipment might have an MOQ of 100-500 units. Digital printing eliminates the need for printing plates, which removes a significant fixed cost component. The trade-off is that digital printing is more expensive per unit than offset or flexographic printing, so the unit price at 300 units might be higher than the unit price at 1,000 units from a large-scale supplier. The procurement team must decide whether the lower MOQ justifies the higher unit price. This decision depends on the buyer's storage capacity, cash flow constraints, and demand certainty. If the buyer cannot store 1,000 units or cannot afford the upfront capital outlay, the higher per-unit cost of a 300-unit order from a digital printing supplier might be the more economical choice.

The supplier's perspective on MOQ is fundamentally protective, not opportunistic. Suppliers set MOQs to ensure that each order generates enough contribution to cover fixed costs and maintain operational efficiency. They are not trying to force buyers to order more than they need—they are trying to avoid accepting orders that will cause them to operate at a loss. When a procurement team offers to pay more per unit for a lower MOQ, the supplier runs the arithmetic and determines whether the increased contribution is sufficient to cover the fixed costs. In most cases, it is not. The supplier declines the order not because they are inflexible, but because accepting the order would be economically irrational. By understanding the supplier's cost structure and focusing on strategies that reduce fixed costs or increase production efficiency, procurement teams can have more productive MOQ discussions that result in mutually beneficial outcomes rather than adversarial negotiations that end in stalemate.

You May Also Like

Rigid Box vs. Corrugated Mailer: Which Material Suits Your Premium Corporate Gifts?

A deep dive into the structural integrity, cost implications, and unboxing experience of rigid boxes versus corrugated mailers for high-end corporate gifting.

Foil Stamping vs. UV Spot: Elevating Your Brand Logo on Custom Gift Boxes

A technical comparison of hot foil stamping and UV spot varnish, analyzing visual impact, durability, and production costs for branded corporate packaging.